[Second post of my End-of-year, now turned New-Year series]

We hardly ever talk about the economic side of softness, or love. And by “we,” I mean women. Especially now, when “love” is being peddled like thrift – the unholy transaction of love for money.

We are shamed for demanding any form of exchange, and for some of us who are constantly fluid in our becoming, even the thought of it makes us cringe.

Shame.

Where does it spring from? Does it even spring?

I believe it calls, whispers, yells, and slaps us atop our heads, because shame isn’t a garment merely thrust upon a person. It is an insidious companion that sneaks in and never leaves. It comes to reside like a shadow, sitting quietly in the corner. That brutal, stern judge that reprimands.

Yep. That’s shame.

“I am ashamed that I’ve given so much without returns.”

“I am ashamed that I can not just walk away.”

These statements may resonate instantly with my audience, because if you read my blog, you must be someone who values presence, kindness, generosity – all the qualities that make love worthwhile.

But what about the shame?

I wish to acknowledge it.

Where does the external shame lie?

In unreciprocated giving, which feels like failure.

It hints at indiscipline, scatteredness, a lack of agency over oneself. And the worst blow of all: low self-esteem.

Then there is the internal shame – the one that gnaws at the limbs like neuropathy: the weakness of not walking away. One that contradicts self-preservation – the absurdity of it all.

That we stayed after understanding the cost.

Not out of morality, but out of attachment. Out of hope. Out of a delayed willingness to withdraw. This is the shame that feels personal, because it implicates agency: a gap between how capable we know ourselves to be, and the execution of it. A gap closed by willpower.

My mother would always say, “We are not business-minded in this family.” And I choose to think of our proclivities in those terms.

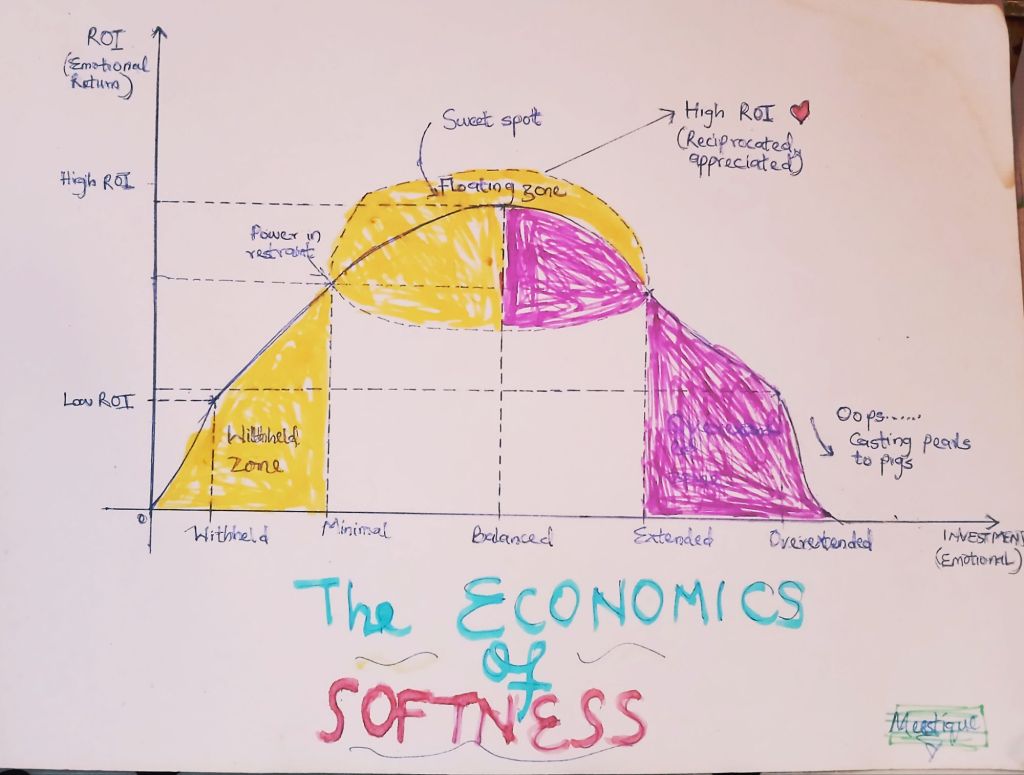

Economics and business have long given language to what we often glaze over, what we decide to ignore. They tell us that when supply increases and demand does not, value falls.

When input continues past its optimal point, returns diminish – then turn negative.

In any negotiation, the party with the strongest alternative to walking away holds the most power.

My dear softies, the ability to leave is not cruelty. It is leverage.

Even as I think on paper, I deduce that shame isn’t always a bad thing, something to be resisted. In this context, it is not moral or personal failure – an affront on one’s self-esteem – but feedback from a mispriced exchange. A reminder that softness, like any resource, requires structure to retain its value. Leaving is not the opposite of love. It is sometimes the condition that makes love possible without forgetting oneself.

Meestique,

– The Empathic Social Observer.