There is a quiet pandemic moving through the relational lives of young people.

It does not look like chaos.

It looks like information.

Endless information.

How to communicate.

How to set boundaries.

How to attract.

How to keep interest.

How to maintain power.

How to avoid being taken for granted.

How to avoid being “too much.”

How to avoid being “not enough.”

Every scroll offers instruction.

Do this to get this result.

If he does this, respond this way.

If she does that, withdraw.

Say less.

Show less.

Give this.

Never give that.

The advice is curated.

Often intelligent.

Sometimes even true.

And yet, it feels like we are under water.

Because somewhere between strategy and self-protection, we have forgotten how to be human.

We are no longer entering relationships.

We are entering performance environments.

“Love is a battlefield,” they say.

And it often feels that way.

We march out, guarded, fighting to conquer emotional territory where we hope to be sovereign – even if it means living there alone.

The choice begins to feel like kingship or captivity.

Yet long before the battle begins, we have already enslaved ourselves to the ideal.

We monitor ourselves constantly.

Am I texting too fast?

Am I too available?

Am I being feminine enough?

Am I leading enough?

Am I maintaining my value?

Am I losing leverage?

Love begins to feel like an exam.

And the unsettling question beneath it all is this:

Who is grading us?

Who is keeping score?

Which standard are we trying to pass?

Because the modern relational world has created a strange pressure:

Not to connect,

but to execute the ideal.

The ideal partner.

The ideal response.

The ideal emotional regulation.

The ideal level of detachment.

The ideal amount of effort.

The ideal knowledge, and tone, and gestures not to create trauma.

Children are divorcing their history- the perfect anology – throwing out the baby with the bath water. Only this time, it’s their aged parents

We are no longer learning how to relate.

We are learning how to optimize.

And optimization, by its nature, leaves very little room for humanity.

Human beings are inconsistent.

We overthink sometimes.

We act too quickly sometimes.

We withdraw when we should speak.

We speak when we should pause.

We get insecure.

We get hopeful.

We get tired of being careful.

But the current relational culture leaves little room for this natural fluctuation.

Every emotional misstep now feels like a strategic failure.

If the relationship struggles, the question is no longer:

What are we feeling?

The question becomes:

What did I do wrong? Which rule did I break?

This is where the real damage begins.

Because, I honestly believe, relationships do need structure.

They need clarity.

They need boundaries.

They need expectations.

They need effort.

But structure without emotional breathing space creates rigidity.

And rigidity suffocates the very thing relationships are meant to hold:

The unpredictable, messy, deeply human experience of knowing and being known.

Of witnessing and being witnessed.

The real challenge is not choosing between structure and emotion.

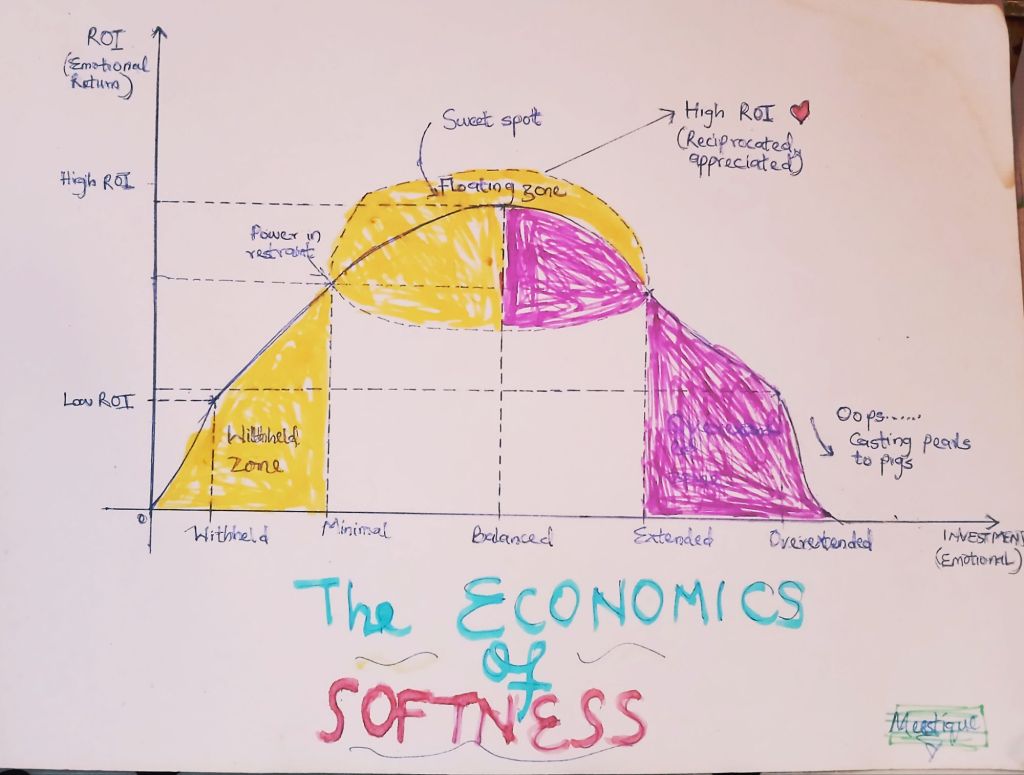

For me, the real challenge is learning how to marry them.

How to hold certainty without losing softness.

How to have standards without turning yourself into a performance.

How to protect your needs without editing your humanity.

Because love does not survive on strategy alone.

It survives in the space where structure meets something harder to define.

That je ne sais quoi.

The warmth that cannot be optimized.

The grace given when someone is imperfect.

The quiet safety of not being evaluated.

The freedom to arrive without calculation.

The tragedy of the current relational climate is not that young people lack knowledge.

It is that e choke. And that we are are slowly evolving into robots.

But if that’s your personal goal, I urge you to continue…

When everything becomes technique, something essential disappears.

The permission to be uncertain.

The permission to be emotional.

The permission to be awkward, hopeful, imperfect, and learning.

The permission to be human.

Perhaps the real relational skill we need now is not another rule.

Perhaps it is the courage to step out of constant self-assessment.

Fear not.

To stop asking:

Am I doing this right?

And start asking:

Is there room for my humanity here?

Because no relationship survives long when both people are trying to pass a test.

The ones that last are the ones where, quietly and without announcement, the pressure lifts.

Where no one is scoring.

Where no one is optimizing.

Where structure exists, but humanity breathes inside it.

Where certainty holds the space.

And the human heart is finally allowed to live, and play, there.

Meestique.

_ The Empathic Social Observer.